Over the past three months we’ve seen politicians presenting statistical charts in prime time. Who would have thought that? We have become familiar with a wide variety of corona metrics and been taught concepts like exponential growth, rate of transmission and predictive modelling that are usually limited to statistics courses at universities.

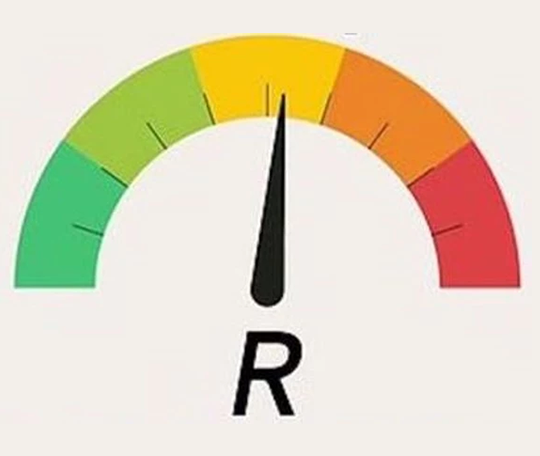

In particular one corona metric has seemed to stand out from the crowd. It is the so-called R-number, which has been at the core of how prime ministers and governors have explained their corona-strategy to the people. The R stands for reproduction and is the number of people one infected person will pass the virus on to, on average. Keep the number below 1, and the outbreak is under control. Allow it to rise above 1, and you will soon face a big problem.